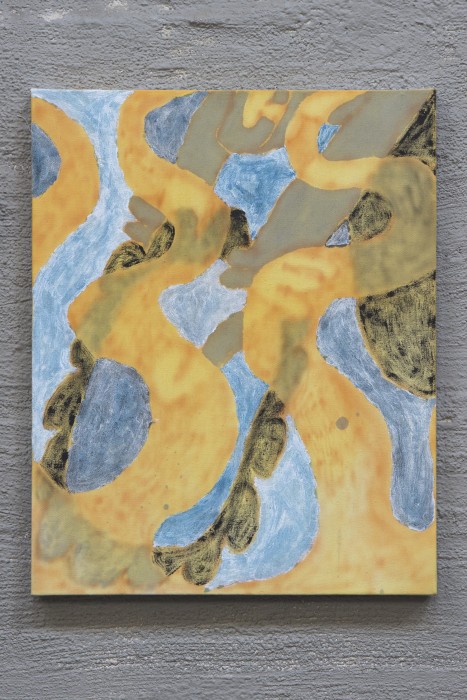

Sarah Abu Abdallah, The Salad Zone, 2013, Saudi Automobil, 2012 and Video Still from The Salad Zone, 2013

Sarah Abu Abdallah works primarily with video and film as a medium. She grew up in Qatif, Saudi Arabia has an MFA in Digital Media at the Rhode Island School of Design. Recent participations include include Prospectif Cinema Filter Bubble in Centre Pompidou, Paris, Private Settings in the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Arab Contemporary in the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, Migrating Forms in NYC, the Serpentine Galleries 89plus Marathon in London, the 11th Sharjah Biennial 2013, Rhizoma in the 55th Venice biennale 2013. Contributed to Arts and Culture in Transformative Times Festival by ArteEast, NYC and the Moving image panel on Video + Film in Palazzo Grassi, Venice. See her catalogue of work on Vimeo here.

Sarah Abu Abdallah studied art in the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia’s more liberal neighbour, making her return to the strictures of life in Saudi Arabia hard. Her film Saudi Automobile tells of her frustration at the ban on women driving. It features a car she found crashed by the side of a road, which she painted pink. ‘This wishful gesture was the only way I could get myself a car,’ she says. “Painting a wrecked car like icing a cake, as if beautifying the exterior would help fix the lack of functionality within the car. This wishful gesture was the only way I could get myself a car – cold comfort for the current impossibility of my dream that I, as an independent person, can drive myself to work one day.”

Saudi Automobil, 2012 depicts Sarah Abu Abdallah painting the shell of a wrecked car with light pink paint, a gesture of defiance against Saudi Arabia’s prohibition on women drivers, which makes mobility the exclusive privilege of men. After sweltering in her abaya under the hot sun, Abdallah finally retreats to the passenger seat, reflecting her place in Saudi society. For the exhibition ‘Soft Power’ Abu Abdallah installed the painted car in the gallery space, further emphasising the limits of her rights to vehicle ownership.

‘I don’t call for extreme freedom,’ she says. ‘But we grow up at a very young age here and the more you grow up the more you realise you will never have full custody of your life.’ Her work, it seems, is Abu Abdallah’s lifeline. She reads about it rapaciously, ordering massive tomes from abroad about abstract expressionism and performance art. ‘Being a woman in Saudi may be really restricting,’ she says, ‘but being a female Saudi artist is very good at the moment. I want to join that wave.’

Sifting through the absolute, the predefined, constructs of anxiety, and the absurdity of the agreed-upon in a time of excess, in her work The Salad Zone, 2013. How does one place one’s coordinates in the physical, metaphysical, and the digital citizenry? It is said that the gravitational forces exerted by the planets affect the circulation of human bodies and emotions as much as they affect the oceans. Youtube and google image search help to assemble an uncomfortable space for a question spanning practices of compulsion and purification. Continuing on a previous question of how in a hyper-connected world, does one place one’s coordinates in the physical, metaphysical, and the digital citizenry. Sarah Abu Abdallah’s series q-VR, draws a mental collage using the everyday, references to virtual reality and old photos of the artist’s father in his youth to make up a fictional world through images.

In her work The Turbulence of Sea and Blood, 2015, we see disarrayed glimpses of multiple narratives such as that of: familial domestic tensions, a juvenile dream of going to Japan, the tendency to smash TVs in moments of anger, and eating fish. While using scenes from the artist’s surroundings and life in Saudi Arabia, like streets or malls, it never attempts to provide the whole picture, but takes a rhizomatic approach to tell a story of the everyday life.

![Rosetta 1999_snapshot_00.14.14_[2012.09.13_23.36.02]](http://www.magazinecontemporaryculture.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Rosetta-1999_snapshot_00.14.14_2012.09.13_23.36.02-1024x616.jpg)